I had been working in New York City for just over a year when I sat down at one of my favorite cafes in my neighborhood to write a personal journal entry. I gave it the title “On the crossroads between goal-oriented and process-oriented” and I wrote down stream-of-consciousness reflections on my life, career, and how I wanted to do things differently.

It was October 2015, and I had finished grad school and moved to NYC to work full-time as a Software Developer in a fin-tech company. I was having what I have come to see as the seminal quarter-life crisis many folks go through when they finish their formal years of education. I had been chasing goals all my life up until then, and now I had the luxury and privilege of deciding whether I should set another goal or do things radically different than what I had done so far. Goal-oriented versus Process-oriented, I called it.

A lot of my thoughts at the time (and those in that journal) have been foundational to my thinking in this new life chapter. Most of those are a story for another time. One I kept coming back to, however, was knowing that I needed to re-engage with doing good in the world.

There are many ways to do good in the world, but I eventually settled on finding skill based volunteering opportunities that used my tech skills as potentially most effective and satisfying. My thinking was: If tech companies put a high dollar amount on my time and skill, wouldn’t giving some of it away be the most effective thing I can do?

This is the story about how I found my path volunteering in tech, how it gave that new chapter of my life new meaning, how I burned out, and what’s next.

Photo by Women of Color in Tech stock images (via Flickr)

Finding my path in Volunteering in Tech

Being passionate about tech and justice, I was interested especially in areas where I can help in issues of equity, representation, and access. I also liked teaching, so my first intuition was looking at programming bootcamps, as well as programs like Girls Who Code, Black Girls Code. Bootcamps appealed to me because they gave an opportunity to work with folks looking to start a career in tech soon and provided access to minoritized people often excluded from the “traditional” STEM pathway. School programs were exciting for different reasons: it’s way more indirect, but it gave the opportunity to inspire a student to consider a totally new path.

One important piece of my situation back then is immigration: I was on an H1-B visa, which meant that my continued ability to live in the U.S. was tied to my job. Therefore, I wasn’t really looking for full-time or sabbatical-type service opportunities.

This ended up excluding most bootcamps at that time. It also excluded the more intense summer programs like the Girls Who Code Summer Immersion Program.

I decided the best match for me at the time was the Girls Who Code Clubs program, which gave me the ability to work with a school in the NYC-area as an instructor in their after-school program. Finally, after a lot of indecision, I ended up applying on Dec 31.

The background screen started on Jan 3. Five days later, I received an e-mail saying I was matched with Chloe Taylor, who was just co-starting a Club at her school. For the coming spring term, I would be helping as an instructor for an after-school club for 5th- and 6th-grade girls interested in coding.

Your Nth reminder that teaching is hard

Everyone tells you teaching is hard, but boy was it hard. I always felt like teaching and mentoring was a core part of me and my passions. I deeply cared about doing a good job. I practiced my very first class again and again, but I don’t think I was truly ready; I underestimated how difficult it would be to command the attention of a classroom. I was used to TA-ing in college where the students needed me, or mentoring co-workers asking for help, but those were adults who had figured out how to manage their attention and distractions. I remember feeling a hard-to-pinpoint—almost embarrassed—sensation after that first club meeting, like I failed at something and was anxious to show my face the next week.

Some of the girls were incredibly excited to code. For others, their parents wanted them to get into it, but they were not yet convinced. They all were eager to try coding! The first good day, where I felt I truly taught and excited them, I was over the moon. But the hard days where I felt like a total failure never really went away.

… and also a charming reminder that my name will eternally cause trouble.

The clubs were set up (at least back then) to meet once a week, have the instructor briefly present a new concept, then work on practice exercises. None of the girls had prior coding experience, so we were using the Scratch programming language1. I would walk around the classroom, with the other teachers (who were themselves picking up coding and doing some of the exercises) and we’d answer questions, check-in on the students, and guide them through their projects.

It was a bit of a trip re-learning how a tween in junior high acts: How they go off day-dreaming mid-sentence or be very single-mindedly focused when something excites them, moving seamlessly between both. It’s incredibly charming! When they got stuck in their coding project, they demanded immediate attention, but if my answer ran a bit too long, they’d have already wandered to the next thought.

We had awesome field trips to the BuzzFeed and Facebook2 offices, heard from folks in tech about their experiences getting into it. BuzzFeed had a panel of people with all sorts of backgrounds entering the field, told us about challenges faced by women in tech, and answered all sorts of questions. Facebook’s free food, snacks, and office design probably made the students more excited about being future engineers than anything I did that year. Whatever does the job, I guess!

As the semester came to a close, we said our goodbyes. I was thankful for the experience and hopeful I might have helped. At that point, I had the sense that teaching younger students was likely not in my wheelhouse. I wanted to get better at it but also knew a trained educator is really what this program needed.

Meanwhile, the Election…

The Javits Center, as taken in 2015, by Ajay Suresh (via Flickr).

You almost forgot all of this is happening in 2016, didn’t you? All this time I had been thinking about “How do I do more good in the world?” I was also facing a feeling of impending doom. The U.S., arguably the world’s first successful experiment in multicultural democracy, was faced with the possibility of heading towards nationalistic, isolationist, and racist populism. Election anxiety was getting the best of me, an experience that was proving to be very, very common.

In August, the answer came to me: DevProgress, a group of volunteers in tech working in loose partnership with the Hillary Clinton campaign to help with progressive causes. DevProgress was effectively a Slack organization, Trello board, and GitHub organization of interested individuals budding off and forming projects with some level of community. Some worked on apps to help organize carpools to vote, others worked with artists making Hillary-inspired art, etc. I applied to join, and by September, I had joined in earnest.

As someone living in the US for 6 years at that point, I cared deeply about where the country is headed. Yet as a visa-holder, I was not allowed to donate to political campaigns, which is traditionally what someone anxious about the election could do. I could, however, volunteer my skills for a campaign.

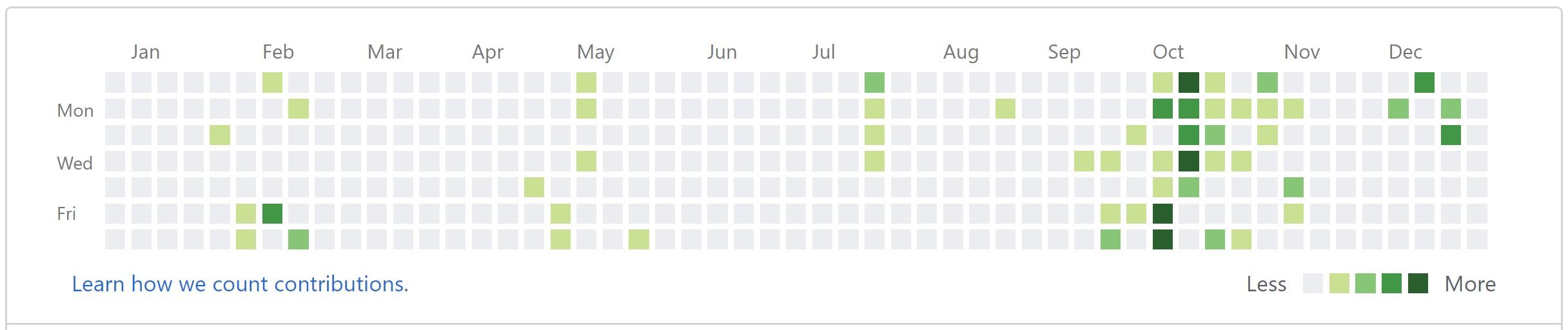

As someone working in a closed-source company, my involvement in DevProgress can be seen very starkly in that brief period in 2016.

I contributed to a few of these projects, and spent countless nights especially helping on a project called “I like Hillary, but…”, aimed at combatting what we perceived as misinformation and innuendo about Hillary Clinton3.

Working with the talented folks of DevProgress was one of the few ways I managed my anxieties in 2016. Things were uncertain, and they were scary—but I could tell myself that I’m doing my best. In retrospect I still wonder if I did my best, or if there’s any small action by one person that could have had a butterfly-effect on the whole election. In the midst of it all, though, it was a particularly good coping mechanism.

Volunteering with DevProgress was always going to end abruptly on November 8, but I was hoping it wouldn’t end devastatingly too. It did, but a lot of the experience is something I keep with me always: Working with a diverse group of passionate people and knowing that my tech skills had value for social issues.

While DevProgress itself became defunct, one of its main leaders Brady Kriss founded Ragtag, which in many ways became the spiritual successor of DevProgress. They’re always looking for volunteers, I suggest you join!

For me, part of regrouping and picking the pieces after 2016 involved a lot of soul searching. I wasn’t ready to face post-Election realities yet, so I held off on joining Ragtag in earnest. But the experience of writing code for good, coupled with another transformative experience that happened around the same time (which I’ll talk about next), lead me down what became my passion for the coming few years.

Building Websites for Good

Around the time I started looking into DevProgress in 2016, I came across a call for volunteers. A non-profit called Out in Tech was launching a new hackathon-type event: Digital Corps. Their announcement read:

Out in Tech is teaming up with Squarespace to build websites for ten (10) organizations fighting to protect LGBTQ+ rights in their home countries, from Pakistan to Botswana.

They announced a one-day event where teams of techy volunteers would build a website for an activist organization working to protect the rights of LGBTQ+ people in their area. I forward this to a few friends, adding “That’s pretty interesting. I’m considering signing up..”

The event was scheduled for a Saturday in September. I wasn’t quite sure how impactful building a website would be, but the idea of doing good using tech appealed to me. They also expressed a need for Arabic speakers, which made it all the more compelling to me to try and help.

The event took place at the newly opened Squarespace offices on Clarkson St in NYC. The space and views were absolutely epic. (Photo © Out in Tech)

That day, what quickly became apparent as my team started working on our website, was just how impactful an online presence can be. These activists were all either in countries where it was illegal or extremely dangerous to be LGBTQ, in incredibly underserved areas, or both.

A website is a safe way for both the brave activists to reach their communities, and for at-risk individuals to get the information they need. A website is a bold assertion of existence in countries that silence and deny the existence of citizens that do not conform. In many cases, the websites we build will be the first affirming resource written in a given native language or dialect. Those websites, with their content written by local activists, will often be the first resource from a local perspective on issues of sexual orientations and gender identity. Those websites, however small they might seem, end up countering the narrative that the modern LGBTQ movement is merely a Western movement.

For people in the west, amplifying voices of local activists is also important to counter homonationalism in Western countries.

Lifting up those voices is important, meaningful, consequential work. I felt that deeply.

The Digital Corps become an army

A few months into 2017, an opportunity came knocking. I was still buried deep in the pits of despair following the 2016 election, too anxious to think about politics and activism. Out in Tech sent out a call asking people to sign up to volunteer on the organizing side.

Digital Crops stood out to me as a dream project I’d love to work on: It is globally minded, fairly activist and political, yet not necessarily directly engaging with the realities of the US political climate which I was hoping not to have to think about it all the time.

And just like that (fast-forwarding a few weeks), I became part of the first group of organizers taking on Digital Corps as a repeatable long-term program. We ended up partnering with Automattic the creators of WordPress. Automattic proved to be the best partner a non-profit can ask for: they offered our partner organizations free Premium and Business hosting and tech support, and they offered our volunteers excellent support as they built these websites, sending Automatticians to provide front-line support as we’re building these sites.

We set up the organizing team into federated groups of organizers each working with one or more activists on understanding their needs prior to the event. We figured out requirements and collected anything we might need: reference information, content, photos, etc., ahead of the event, then worked on selecting volunteers and getting them up-to-speed on the day of.

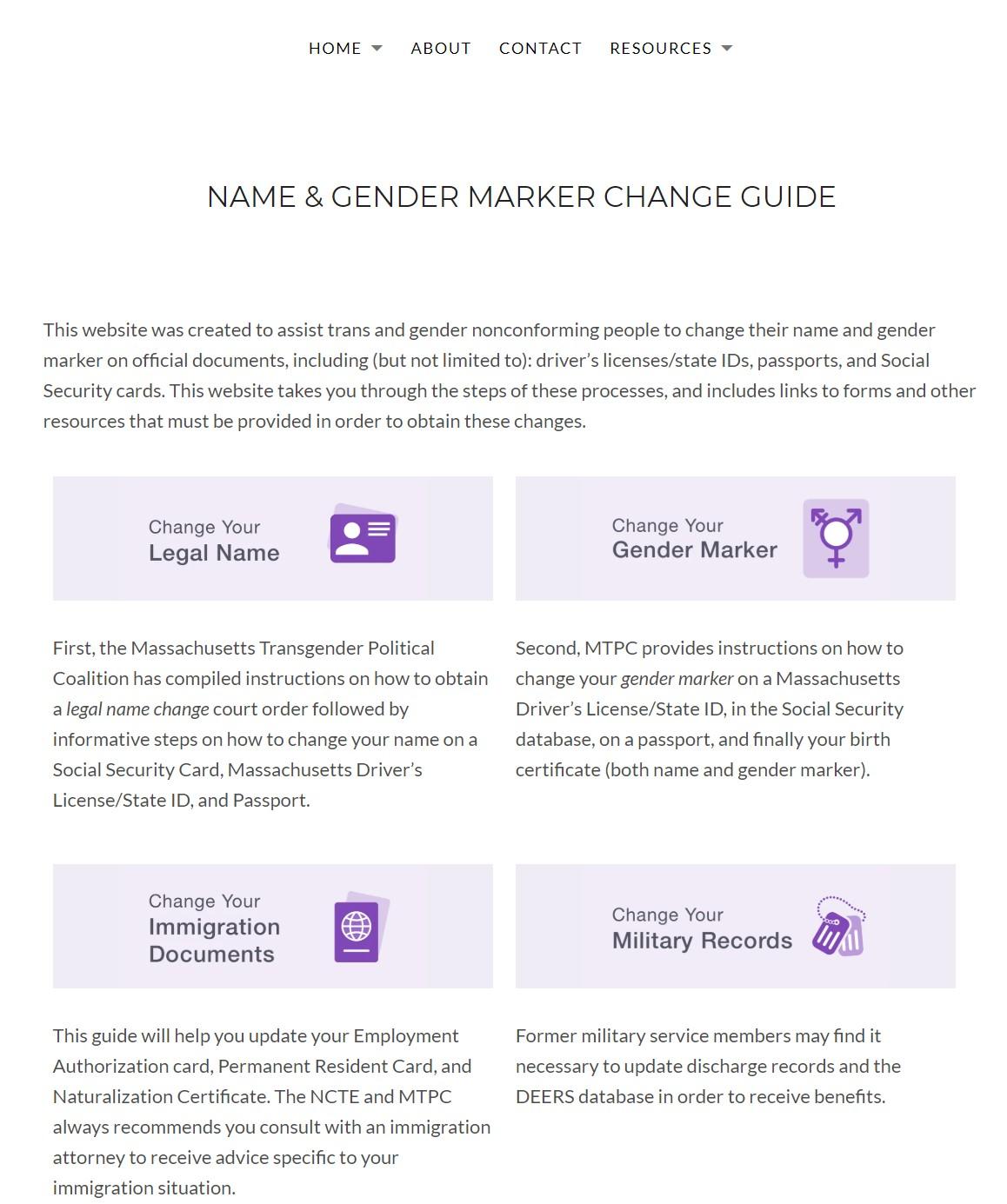

My first ever project was working with the Massachusetts Transgender Political Coalition (MTPC) on creating a Name & Gender Marker Change Guide for people navigating this incredibly difficult process in Massachusetts. The result was gorgeous and thoughtful, in no small part to Rita de Almeida a volunteer on the team. Rita is also an artist, UX designer, and researcher. She soon also became the goddess of Digital Corps, heading the entire organizing effort.

The first event I helped organize in June 2017 was a success. It gave me great confidence that the “magic” I felt working on one website was repeatable, and with it the potential for a positive impact on the activists around it.

Things weren’t perfect right away, we were still trying to understand: how to scope projects so they fit in a day; what level of maintenance should we expect the organizations to do themselves; what level of support should we offer them; and more. We tried working with a large multinational organization to extend their Drupal/Salesforce pipeline and quickly learned that self-contained projects have a way higher chance to succeed than incremental pieces in large projects.

We also learned that WordPress powers 30% of the world’s websites for a reason: It’s maintainable and accessible for all users, while still highly customizable by web developers.

With that, from 2017 until 2020, I’ve worked on 10 or so of these events (Digital Corps tries to hold 3-4 events/year across the world). Each of those events is quite a big production: From logistical event planning, marketing, volunteer recruitment and selection, to finding and vetting partner organizations, working with them on their requirements, and making sure we have the needed requisites to build them a high-quality presence.

Working with these organizations over the last few years was among the most meaningful work I had done.

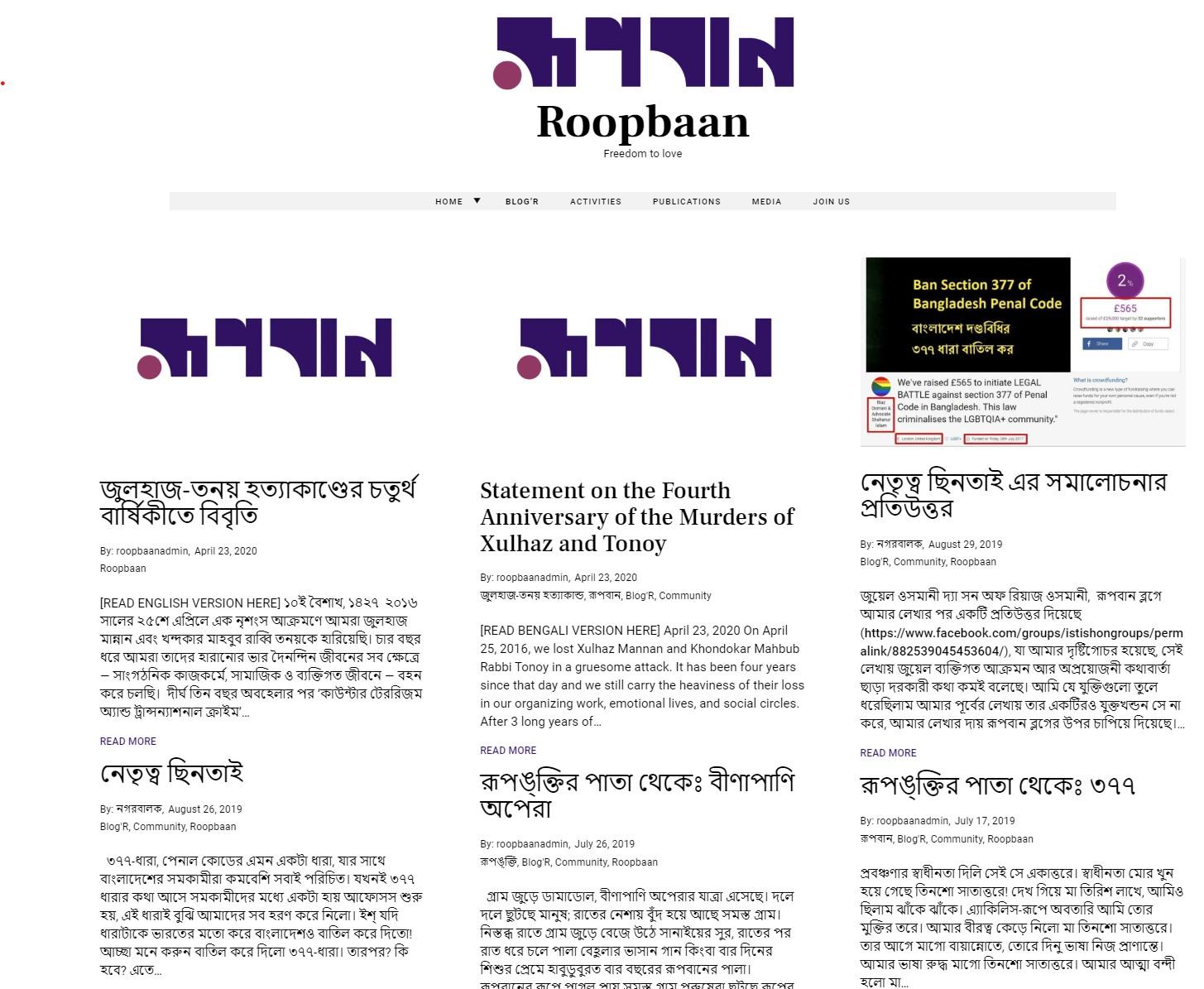

I worked with Roopbaan, Bangladesh’s first and only LGBT magazine. It was founded by hero and activist Xulhaz Mannan. Mannan first published Roopbaan in 2014, and the magazine rose to prominence (as well as infamy) in Bangladesh. Xulhaz was murdered in 2016, along with fellow activist and Roopbaan member K Mahbub Rabbi, abruptly putting a stop to the magazine. I learned all this from Mannan’s activist friends and colleagues, who wanted to continue the Roopbaan effort online where it could not be silenced by those who wanted to.

I worked with the African Queer Youth Initiative on creating their website and online presence, and watched them grow their website and blog into a respected authoritative perspective on issues impacting queer youth in Africa.

I worked with Outcasts Tunisia in developing one of the first Arabic-language transgender-affirming resources in the Maghreb region.

Those, and many more, inspired me daily to the best I can do between working hours and on weekends. I took calls at odd times, working across many time zones, meeting new organizers and activists hoping to make their local communities better, against all odds.

I also met countless volunteers who are passionate about making a difference. Folks who decided to show up at 9:00 AM on a Saturday4 at some brightly-lit tech office to work on some websites. They’re internationally-minded, many hailing from all over the world, and all passionate about giving back. I’m grateful today to call many of those people good friends.

What makes Digital Corps successful?

Volunteer efforts almost always suffer from friction, a lack of motivation, and fundamental challenges with initiative-taking. It’s easy to sign up to do something, but it’s just as easy to procrastinate doing it. Saying “I’ll do this thing” feels good on its own, so when it comes time to reply to that e-mail or decide what project to work on, you might just wait for someone else to do it—or just postpone it a little.

From my experience, every volunteer-based organization I’ve seen suffers from this.

From my perspective, the Digital Corps program sidesteps this by making so much of the action self-contained within a single build day. We just ask our volunteers to show up on a given day (and have a certain skill set), and we count on them to work as they’re energized by the colleagues around them.

Seeing these organizations and the impact associated with their work is incredibly meaningful. People are proud of the work they’re done, rate the event highly in surveys, and will often apply for future events and tell their friends about it.

Effectively, we retain a highly motivated, highly skilled population of volunteers by shifting a lot of the day-to-day engagement work into organizers. The organizers in turn work to define a self-contained single-day deliverable for these volunteers.

Burning Out

One downside to the Digital Corps model is that it might be easy to burn out as an organizer. At least that’s what happened to me. Working on something meaningful on tight deadlines with a rather short periodicity (once every few months) is a bit of an emotional rollercoaster. You get to know a set of activists and invest your relationship with them. You race against the clock figuring out requirements, structure, content, etc. It culminates in a huge event that hopefully goes swimmingly. Then you’re back to square one.

The periodicity of it really affected me. Especially as I tried to balance work and other volunteer commitments.

My work with Digital Corps helped me survive and come to terms with the new realities of the post-2016 era. It spanned an apartment move, two jobs, and a few promotions. I joined Digital Corps when I was just about checked out with the world around me, and it snapped me out of it.

Yet as 2019 went by I was becoming more fatigued and checked out. It’s a really weird experience when the thing that brought you back from detachment is making you more detached.

Part of this was that my first few years with Digital Corps involved me coasting at a fin-tech job then joining Google and ramping up. Ramping up isn’t quite the same as coasting, but there are overlaps with it often being less high-stakes which helps keeping volunteering involvement front-and-center. It felt easy to be an engaged volunteer coasting at work, but it was much harder trying to do both. It felt like my full-time job, though not quite a do-good profession in the same way, had its turn to come first.

Thinking Ahead

Today, I maintain some minimal involvement in Digital Corps. I keep wanting to explore being more active, but with the pandemic upon us in all its glory, it’s now harder than ever to think about how to stay motivated with what you’re already doing.

As I wrote this, I had questions on my mind that I hoped spelling this out would answer: What are the decision points for re-engaging now or later? What circumstances might need to be in place for me to re-engage in a different capacity?

I was disappointed the answer didn’t come to me. I sent an early draft of this to friends hoping for perspective. Here are some proposed parameters:

- Dive back in again and then accept the inevitability of burning out (again)

- Angle for a career shift within Google to get paid to do “good” (not just do-no-harm work) work?

- Does having a green card mean you can donate to political causes? If so, it might be time to take the rich person offramp and donate as a way of exercising your values.

- Can you look for avenues in Digital Corps for a smaller amount of contribution?

- Focus on a different area of volunteering so you can chase the high of being a newbie again and ride that wave until the next trough finally hits.

Embracing burn-out as a (sometimes) inevitable part of the process and working with it resonates. We all burn out and work, but it rarely means we’re forced into early retirement.

Google, for its part, does have the Google.org Fellowship, where employees effectively take a sabbatical from their role to work with non-profits that need that work. This, and other types of sabbaticals, are definitely appealing. Working out the timing (especially when putting work on hold might slow down your career advancement) and figuring out the right trade-off remains something I haven’t mastered there.

Donating should absolutely become part of the wider picture of wanting to do good. Donating competes with buying other goods for money, but it doesn’t really compete on time with other commitments per se. If I can, I’d still love to do both.

I also need to answer questions about what and how much. Can I find smaller meaningful chunks that I contribute? Would those fit in the common volunteering model where it is harder to come up with self-contained tasks that need work than it is to do the work for those tasks? Will working in a new area re-inspire me in ways where I might have gotten numb5?

I’m still not sure what looks ahead. But soon enough the pendulum will swing from burnt out to restless, and the cycle will start over.

If my discussion on Digital Corps excites you, please consider applying for their coming events! Their mailing list will inform you of upcoming opportunities.

If this resonates, I’d love to hear what you think. Tweet at @EyasSH. Or, be sure to sign up to get updates on future articles.

Footnotes

-

A more advanced course with Python was also available. ↩

-

They made sure to tell all their friends they were going to the Instagram offices. It was cooler. ↩

-

We later found out how much of that misinformation was carefully amplified through bot rings, fake profiles, and strategic online advertising targeting both right- and left-leaning voters. ↩

-

This is tech we’re talking about, so 9:00 AM on a weekend is early. ↩

-

Analogous to compassion fatigue, if you will. ↩

Winding Path by Phil Bulleyment, via Flickr

Winding Path by Phil Bulleyment, via Flickr